Market analysts believed baby boomers were likely to purchase more diet drinks as they aged and remained health- and weight-conscious. Therefore, any future growth in the full-calorie segment had to come from younger drinkers, who at that time favored Pepsi and its sweetness by even more overwhelming margins than the market as a whole. When Roberto Goizueta took over as CEO in 1980, he pointedly told employees there would be no sacred cows in how the company did its business, including how it formulated its drinks. Coca-Cola's most senior executives commissioned a secret effort named "Project Kansas," headed by marketing vice president Sergio Zyman and Brian Dyson, president of Coca-Cola USA, to test and perfect the new flavor for Coke itself. It took its name from a famous photo of that state's renowned journalist William Allen White drinking a Coke that had been used extensively in its advertising and hung on several executives' walls. The company's marketing department again went out into the field, this time armed with samples of the possible new drink for taste tests, focus groups, and surveys.

The results of that were strong — the high fructose corn syrup mixture overwhelmingly beat both regular Coke and Pepsi. Then tasters were asked if they would buy and drink it if it were Coca-Cola. Most said yes, they would, although it would take some getting used to. A small minority, about 10-12%, felt angry and alienated at the very thought, saying that they might stop drinking Coke altogether. Their presence in focus groups tended to skew results in a more negative direction as they exerted indirect peer pressure on other participants.

The surveys, which were given more significance by standard marketing procedures of the era, were less negative and were key in convincing management to move forward with a change in the formula for 1985, to coincide with the drink's centenary. But the focus groups had provided a clue as to how the change would play out in a public context, a data point that the company downplayed but which was to prove important later.

Management also considered, but quickly rejected, an idea to simply make and sell the new flavor as yet another Coke variety. The company's bottlers were already complaining about absorbing other recent additions into the product line in the wake of Diet Coke. Many of them had sued over the company's syrup pricing policies. A new variety of Coke in competition with the main variety could, if successful, also dilute Coke’s existing sales and increase the proportion of Pepsi drinkers relative to Coke drinkers.

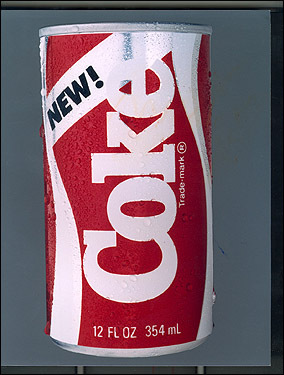

Early in his career with Coca-Cola, Goizueta had been in

charge of the company's Bahamian subsidiary. In that capacity,

he had improved sales by tweaking the drink's flavor slightly,

so he was receptive to the idea that changes to the taste of

Coke could lead to increased profits. He believed it would be

"New Coke or no Coke", and the change must take place openly. He

insisted that the containers carry the "NEW!" label, which gave

the drink its popular name.

that capacity,

he had improved sales by tweaking the drink's flavor slightly,

so he was receptive to the idea that changes to the taste of

Coke could lead to increased profits. He believed it would be

"New Coke or no Coke", and the change must take place openly. He

insisted that the containers carry the "NEW!" label, which gave

the drink its popular name.

Many of New Coke's problems developed during the rollout. Archrival Pepsi was able to undermine the public relations push, and Coke's own executives, particularly Goizueta, did not impress the media.

Coke let the media know on April 19, 1985 that a major announcement was planned for the following Tuesday, April 23, concerning a change in the product. While its press release did not explicitly say so, many recipients correctly guessed it meant a change in the flagship brand's formulation. So, too, did officials at PepsiCo, who had expected a major move but not something so drastic.

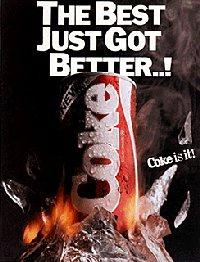

Despite a negative reaction by top Pepsi executives to a smuggled preview six-pack of the new flavor, they nevertheless concluded it was a serious threat. Roger Enrico, then director of North American operations, wasted no time taunting Pepsi's older rival. He declared a companywide holiday and took out a full-page ad in The New York Times proclaiming that Pepsi had won the long-running "cola wars". Since Coke officials were preoccupied over the weekend with preparations for the big day, their Pepsi counterparts had time to cultivate skepticism among reporters, sounding themes that would later come into play in the public discourse over the changed drink. The next day Pepsi gave every employee the day off in celebration of their "victory" over Coca-Cola, claiming their successful brand forced the drastic change for Coca-Cola.

New Coke was introduced on April 23, 1985. Production of the original formulation ended that same week. The press conference at New York City's Lincoln Center to introduce the new formula did not go over very well. Reporters present had already been fed questions by Pepsi, which was extremely worried that New Coke would erase all its gains. Also, Goizueta's description of the new taste, given his background as one of the company's flavor chemists, was less than impressive: "[It's] smoother, uh, uh, rounder yet, uh, yet bolder . . . a more harmonious flavor."

Goizueta defended the change by pointing out that the drink's secret formula was not sacrosanct and inviolable. (As far back as 1935, Coca-Cola sought kosher certification from an Atlanta Rabbi, and made two changes to the formula so that the drink could be certified kosher [and, incidentally, Halal and vegetarian] and also Kosher For Passover.)

But Goizueta also refused to admit that taste tests had in any way led the company to make the change (which he called "one of the easiest decisions we have ever made") to avoid giving Pepsi any credit, yet gave no other real reason for the change, further alienating reporters who had already heard from Pepsi representatives in advance on this very issue. A reporter asked whether Diet Coke would also be reformulated "assuming this is a success," Goizueta curtly replied, "No. And I didn't assume that this is a success. This is a success".

The emphasis on the sweeter taste of the new flavor also ran contrary to previous Coke advertising, in which spokesman Bill Cosby had touted its less-sweet taste as a reason to prefer Coke over Pepsi. Nevertheless, the company's stock went up on the announcement, and market research showed that 80% of the American public was aware of the change within days.

While it is widely believed today that the new drink failed

almost instantly, this was not the case.

The company, as it had

planned, introduced the new formula with big marketing pushes in

New York (workers renovating the Statue of Liberty were

symbolically the first Americans given cans to take home) and

Washington, D.C. (where thousands of free cans were given away

in Lafayette Park). Sales figures from those cities, and other

regions where it had been introduced, showed a reaction that

went as the market research had predicted. In fact, Coke's sales

were up 8% over the same period the year before.

The company, as it had

planned, introduced the new formula with big marketing pushes in

New York (workers renovating the Statue of Liberty were

symbolically the first Americans given cans to take home) and

Washington, D.C. (where thousands of free cans were given away

in Lafayette Park). Sales figures from those cities, and other

regions where it had been introduced, showed a reaction that

went as the market research had predicted. In fact, Coke's sales

were up 8% over the same period the year before.

Most Coke drinkers resumed buying the new drink at much the same level as they had the old one. Surveys indicated, in fact, that a majority liked the new flavoring. Three-quarters of the respondents said they would buy New Coke again.

Despite New Coke's acceptance with a large number of Coca-Cola drinkers, a vocal minority of them resented the change in formula and were not shy about making that known — again just as had happened in the focus groups.Many of these drinkers were Southerners, some of whom considered the drink a fundamental part of regional identity. They viewed the company's decision to change the formula through the prism of the Civil War, as another surrender to the "Yankees". Company headquarters in Atlanta started receiving angry letters expressing deep disappointment and anger at executives. Over 400,000 calls and letters were received by the company. A psychiatrist Coke hired to listen in on phone calls to the company hotline, 1-800-GET-COKE, told executives some people sounded as if they were discussing the death of a family member.

They were, nonetheless, joined by some voices from outside the region. Chicago Tribune columnist Bob Greene wrote some widely reprinted pieces ridiculing the new flavor and damning Coke's executives for having changed it. Talk show hosts and comedians made light of the switch. Ads for New Coke were booed heavily when they appeared on the scoreboard at the Houston Astrodome. Even Fidel Castro, a longtime Coke drinker, contributed to the backlash, calling New Coke a sign of American capitalist decadence. Goizueta's own father expressed similar misgivings towards his son; the only time the younger man recalled him ever agreeing with Castro, the man whose revolution had driven him and his son, nearly penniless, to America a quarter-century before.

Pepsi took advantage of the situation, running ads in which a first-time Pepsi drinker exclaimed "Now I know why Coke did it!" However, Pepsi actually gained very few converts over Coke's switch, despite claiming a 14% sales increase over the same month the previous year, the largest sales growth in the company's history. The most alienated customers simply refused to buy New Coke rather than switch to Pepsi. Coca-Cola's director of corporate communications, Carlton Curtis, realized over time that they were more upset about the withdrawal of the old formula than the taste of the new one.

The new product continued to be sold and retained the name Coca-Cola (until 1992, when it was officially renamed Coca-Cola II), so the old product was named Coca-Cola Classic, more commonly Coke Classic and later just Coke.

"There is a twist to this story which will please every humanist and will probably keep Harvard professors puzzled for years," said Keough at a press conference. "The simple fact is that all the time and money and skill poured into consumer research on the new Coca-Cola could not measure or reveal the deep and abiding emotional attachment to original Coca-Cola felt by so many people."

The company gave Gay Mullins the first case of Coke Classic.

Coke spent a considerable amount of time trying to figure out where it had made a mistake, ultimately concluding that it had underestimated the public impact of the portion of the customer base that would be alienated by the switch. This would not emerge for several years afterward, however, and in the meantime the public simply concluded that the company had, as Keough suggested, failed to consider the public's attachment to the idea of what Coke's old formula represented.